The Canada Council for the Arts publication of a major report on the state of the visual arts in Canada (discussed here) inspired us to look afresh at how social enterprise concepts might play in the arts. This quote from the report was the spark: “[M]uch can be learned from innovative strategies in start-up culture, social enterprise and experimental development; as well as emergent non-profit business models that are being explored across other sectors.”

The Canada Council for the Arts publication of a major report on the state of the visual arts in Canada (discussed here) inspired us to look afresh at how social enterprise concepts might play in the arts. This quote from the report was the spark: “[M]uch can be learned from innovative strategies in start-up culture, social enterprise and experimental development; as well as emergent non-profit business models that are being explored across other sectors.”

What are the startup and social enterprise strategies the report is referring to? And what is to be learned from them?

The mantra of social enterprise is “people, planet and profit.” And for both startups and social enterprises, success has to be measurable, producing both social and financial returns for investors and the enterprise.

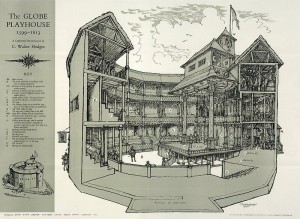

Social enterprise is defined in this this Reuter’s article as “a business that solves a social purpose.” The article is about the UK’s Globe theatre raising £5m (CAD $7.5m) through a “social impact bond” (SIB) issue.

Social enterprise is defined in this this Reuter’s article as “a business that solves a social purpose.” The article is about the UK’s Globe theatre raising £5m (CAD $7.5m) through a “social impact bond” (SIB) issue.

The UK government has 31 SIBs as of this year, more than there are in the rest of the world combined. A government issued SIB is typically calculated to produce a return on investment in the form of savings on how government is currently doing things. For example, a bond issued to support home care over hospital care, will produce savings in overall health care costs. As performance goals are met, bond holders receive financial returns proportional but not eating up all the savings. Everybody wins, maybe not as much as in the private investment world but enough to make a difference.

For Shakespeare’s Globe theatre, it is not yet clear whether the bond will be designed to produce actual financial returns or is more like philanthropy by a sexier name. But in terms of “social return on investment” or “social impact” the Globe’s impact looks impressive: in the first six months of a 24-month world tour launched in April 2014, 89 performances of Hamlet were staged in 54 countries to approximately 54,000 people.

Taking social enterprise literally

A more literal approach to using startup and social enterprise strategies would be to try them out. There are a host of enterprising things museums do already. To be strategic, pushing toward the triple bottom lines of people, planet and profit, would take just a little tweeking:

Hospitality Industry Training

Typically, services in public institutions like museums and art galleries are “extra.” The primary tasks are to collect and preserve and present artifacts or art. Guests are welcome but secondary to the primary mission. Financing similarly is not tied to the mission. There’s a correlation of course between donors, sponsors and visitor support and the quality of program but it is indirect. No-one buys a curator’s decision to show a particular artist, least of all the public.

All that is fine, but when it comes to visitor services, public galleries have learned that numbers matter and holding numbers requires more than simply delivering great exhibitions in great, well-kept spaces. Increasingly, they are required to pay attention to the “visitor experience.”

Receptionists and docents know just how often they are asked for directions to restaurants or other attractions. Yet, few people working in the arts are properly trained in how to anticipate and respond to visitors. This is the territory of “customer relations,” and “hospitality,” familiar in the travel and accommodation industries. This is not to say that today’s museum goer is not welcomed and helped. They are. And museums are increasingly attentive to, and developing expertise in this area.

At the same time, there is also a need for trained people in the tourism and hospitality fields. As Richard Florida pointed out over a decade ago, the whole economy has shifted toward services. As manufacturing moves offshore and leisure becomes more important for a larger, aging and relatively financially secure demographic, services training is needed.

Museums could strengthen and broaden their public role by focusing on, and enhancing, visitor services. To be able to invest in improved services, an entrepreneurial approach could be taken. Museums could create visitor centres that are a training grounds for tourism and hospitality workers. They would simultaneously get the benefit of the people learning on the job while also producing people with experience and enthusiasm who are 100% more likely to search out or even create new opportunities to put their greeting/hosting/serving skills to use.

Official Guide Training Program

In the UK, Blue Badge guides are among the most respected people working in the hospitality and tourism industry. The training is rigorous: they study for up to two years at university level, taking a comprehensive series of written and practical exams which qualify them to become Blue Badge Tourist Guides.

Art museums already train and use docents, and increasingly are looking at digital audio/media supports for the visitor experience. For sure, digital media are intriguing, for now, but nothing compares to the caring and knowledgeable personal guide. A program that trains people, older and younger, to develop their knowledge and presentation skills to encyclopedic levels would prove its value in two concrete ways: enhancing workforce skill levels but also by adding credibility and respect to the institutions that would employ those people. In the highly competitive tourism marketplace, distinctiveness and quality are prized and hard to achieve.

Art Bank

Started in 1972, the Canada Council Art Bank was as innovative a social enterprise concept as you are ever likely to find. Artists would “bank” their work there, having been paid well for it, retaining a right to “withdraw” it at any time for the same price. The presumption was that years later, the value of the work having gone up substantially, the artist would be able to buy the work back at cost and sell it, capitalizing on the increased market value.

For the Art Bank, the money wasn’t in the escalating price of the work but in renting it out while they held it. Government and corporate offices throughout Ottawa showcased the best work being done in Canada. It was stunning and a model that worked fabulously well for many years, producing surpluses year after year. Eventually, however, the model failed. The vaults kept growing, storage and maintenance costs ever increasing, but the rental market was saturated and redemption was rare. Most Canadian art isn’t worth more than it was the day it left the studio.

Today the Art Bank is still struggling to find its way. But it has created a fine history of respectable failures to learn from. One obvious lesson is that an enterprise that hopes to succeed in the marketplace needs to have the agility to move with it. Failing to change its art acquisition policies when the rental market was saturated (and in fact started to collapse as government cost cutting eliminated rental budgets) was fatal.

The most important lesson of the Art Bank lies in the relationship between collection and marketplace. Many art galleries have rental services but the work they rent is generally not very valuable and not very good. One assumes the reasons, risk of damage, theft, insurance costs. Yet the Art Bank was able to place artwork valued in the 10s of thousands in public and private buildings, often in high traffic areas. Why shouldn’t artworks in museum collections be rented out directly to conscientious patrons, businesses, organizations and local government?

Or how about this even more radical idea? Imagine a dystopian Fahrenheit 451-ish future in which collections are distributed among the people, housed and cared for piece by piece; it would be the “museum” as it started, with the impulse to collect, conserve, study, only distributed and organized as we are able to do now in the 21st C.

Sunday Painters

The art world has spent the past 30+ years learning not to judge everything from the white European male perspective. Just as barriers to women, black, hispanic, gay and other artists of all kinds fall, perhaps the final frontier of inclusiveness will be opening the doors of privilege to the genre and amateur artist.

It is difficult for art museums to show local amateur artists, except maybe once a year, in hallways. Wildlife artists like Robert Bateman continue to be ignored despite their global popularity. What’s going on? It’s not like the “high arts” can’t handle a challenge. In fact, critical challenge is what the best of the arts are supposed to be good at. As Andrew Hunter, now curator of Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, showed in his early curation-as-art practice, art is liminal, an effect produced at the interstices of place, object, object and encounter, i.e. contextual.

I know it sounds improbable, but the assumptions around things like Sunday (and other genres of) painters warrant testing. There is something so obviously “social” in these practices. And engaging audiences more as active producers than passive spectators can’t be a bad thing. It’s a clumsy idea. It’s unclear where the “enterprise” part might come in. Some amateur work is produced in gallery art classes for which the artists already pay. Wildlife or naturalist artists like Bateman would draw staggering numbers of visitors of course, selling out the gift shops. I have no conclusions in this final example. I’m just throwing it out there. Perhaps you see it more clearly.

The point of this exercise, these four ideas, has been to look at things differently. Social enterprise is about finding ways to accomplish important social purposes in ways no one has thought of before. It’s willing to risk failure for the chance to do something unprecedented and remarkable.

In startup land, there’s a lot of buzz around concepts like “disruption.” Many things that we assumed had to be the way they were, aren’t that way anymore, bookstores for example. This kind of change may not always be good, at least not in the way we have defined “good,” but it is always interesting, which is, as artist Don Judd once said, the whole point.