Impact is a word you hear often these days. For social enterprises, non-profits and charities it tends to be teamed up with “social,” as in “social impact,” referring to the good you are doing. For business it tends to be partnered with “economic,” as in how much money you make, how many people you employ, plus also how your business stimulates other businesses, contributes to consumer spending power and the overall economy (GDP). Most of us would like to think they are the same thing: that qualitative effects can be evaluated in terms of quantitative results or even dollars, but that isn’t always the case, and I don’t think it should be, if only for the sake of clarity.

We recently completed a business plan for a non-profit community organization that needed to show its funders that it has capacity for real economic growth that will help it be financially sustainable for the long-term. Our research found that, while it will never be free from needing grants, it has a strong track record of private support from donors and sponsors, which when coupled with consistent results in winning grants makes it possible to predict with confidence that it has capacity to do more, to grow these sources of revenue and diversify them. We also found considerable potential to increase self-generated revenue from existing programs and by adding new facilities and programs. Here, however, even though we were talking about very concrete, business-like things, it was difficult to project results with confidence. Two things were lacking: data about how the organization is already working from a program/services earnings perspective, and in-depth understanding of the marketplace, who and how it is serving.

These are concrete and measurable things but the reality is that most non-profits haven’t the time to stop and gather data about their programs or the inclination to study the community they serve as if it were a market, evaluating what is working to determine how to improve or what more/different might be needed. Intuition tends to guide them and quite reliably so, thanks to the caring expertise of the people who work there. But in today’s world where measurables and milestones are the order of the day, more is needed.

I think there’s some fear that using business tools (for looking at social enterprises from a market and revenue perspective) is like joining the “forces of darkness,” that principles, mission and ethics will be compromised the moment you associate dollars with them.

Before you judge, it is worth looking at the tools, some of which have been developed by the communities that use them to help put dollar values on the indirect “intangibles” that non-profits deliver. One example, is this calculator created by Americans for the Arts (AFTA).

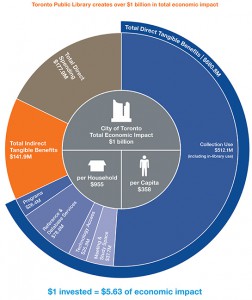

Economic impact calculators use multipliers based on detailed study of various industries. The AFTA calculator produces suspiciously big numbers for indirect and “induced” (even less direct, like ambient) impacts of arts organizations like museums, until you consider that cultural industries actually produce bigger impacts than traditional industries like manufacturing. The multipliers used for the auto industry, for example, take into consideration indirect impacts on parts manufacturers and materials suppliers and even less direct (“induced”) impacts on industries that in turn supply them. But arts organizations engage more and more varied kinds of industries, many of which are closer to the surface of consumer society. Impacts are felt far beyond supply, in adjacent creative industries like fashion and design, and flowing right through to consumer products and the media; film, television and new media. (As discussed in this UK study.)

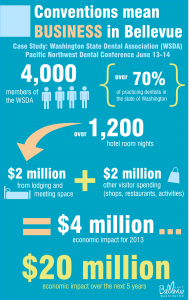

Another interesting tool to look at is a calculator called the Tourism and Recreation Economic Impact Model (TREIM) created by the Government of Ontario. Its multipliers are much smaller than those used by AFTA, but still produce impressive numbers for organizations for whom audiences or visitors are a primary driver. Audiences are measurable and so are their impacts, and organizations can set goals for themselves, milestones that will verify their assumptions and validate their strategy, or, if the numbers don’t materialize the way you hoped, allow you to course correct and try something else, just like businesses do.

In the end, the important thing is not whether you have 15 or 500 people you serve (clients, customers, visitors or whatever) but whether you can verify the number before you start and measure how it changes because of your program or project. If you can do that, and measure other impacts, you will not just be satisfying a funder’s seemingly arbitrary requirements; you will find it useful, helping you to do a better job achieving the goals you set.